Middle English (1066—c.1485) developed after the French-speaking Normans conquered England in the year 1066. Over time, English commoners would combine the German vocabulary and grammar of Old English with the type of French vocabulary and grammar spoken by their new Norman rulers.

This marriage of languages produced many children: “Middle English” is actually an umbrella term for a whole host of different English dialects born during a time of rapidly changing English between the years 1066 and 1485.

When William Caxton brought the first printing press in England to London, he chose to publish Geoffrey Chaucer’s manuscript The Canterbury Tales on it, making Chaucer’s London dialect of Middle English the standard for English from 1476. Nine years later, Caxton would print Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, the first published book discernible as Early Modern English, in 1485.

English monarchs, strange as it may seem, would speak French in the English court for hundreds of years after William the Conqueror took the throne in the eleventh century. Meanwhile, England’s commoners continued to speak their vernacular English, a language that would develop and change dramatically until English made its big comeback among the upper class, when the English royals began speaking it, late in the 1300s.

Middle English, the Great Mutt

Middle English was an improvised language, a hodgepodge of Germanic and French vocabulary, syntax, and grammar. It is a mutt. (Our word “mutt” itself would not exist without the fancy new Middle English “mutton” becoming a synonym for the Old English “scep” [sheep]. Baa!)

One version of Middle English, however, branched off and developed into Scots, a language (and alternative version of English) still spoken in Scotland. John Barbour’s The Brus (about Scotland’s King Robert the Bruce) is a representative work of this early branching off into Scots, dating to about 1375.

Middle English, the Great Bridge

Middle English was a rapidly changing language, a great, transformative bridge between Old English and Early Modern English, and it is far closer to the English of today than the language of Beowulf.

Obvious exceptions are that the Middle English ‘r’ was spoken with a roll (still heard in Scotland now), there were no silent letters as in Modern English, and the ‘-e’ and ‘-ed’ endings of words were pronounced, unlike their silent or elided counterparts in Modern English. If something happened, it really happen-ed.

The pronunciation of some English vowels, also, started to change dramatically by the end of the Middle English period, culminating in The Great Vowel Shift (c.1400-c.1700). Short vowels in Middle English sounded much like ours still do, but the long vowel sounds began in Modern English to shift upward in the mouth.

In short, remember: Beowulf is Old English, The Canterbury Tales is Middle English, and Hamlet is Modern English. The next time you hear someone refer to William Shakespeare as a writer of “Old English,” you will know they are not thinking like a reader. Help them out.

What was The Great Vowel Shift?

Danish linguist Otto Jespersen first identified and named what he called “The Great Vowel Shift” in a book called A Modern English Grammar Based on Historical Principles (1909). Jespersen argued that English speakers dramatically changed the way they pronounced long vowel sounds, and that this change transformed the language rapidly over three centuries—from around 1400 until the vowel shift slowed sometime around 1700.

So, while Middle English literature’s diction and syntax look much more like our own than their Old English equivalents, the long vowels sounded very different.

The biggest difference when learning to read Middle English works will be learning to pronounce those long vowels from before The Great Vowel Shift:

Our long ‘A’ sound would be spelled in Middle English “e” or “ee.” This version is called the “close e,” sounded with the tongue closer to the roof of the mouth. The Middle English pronoun “me” or vegetable “beet” would have pronounced vowel sounds as in the modern “may” or “bait.” Our ɛ sound, as in “wet,” also would be spelled in Middle English with an “e,” but this version is called the “open e,” as the tongue is lower in the mouth making the ‘e’ sound more open. It is much more recognizable to contemporary ears. The Modern English word “red” and the Middle English spellings “red,” “ret,” or “redde” should not be too intimidating (but do not forget to roll the ‘r’). Our long ‘E’ sound would be spelled in Middle English “i” or “y:” Middle English “sight” or “myne” would have vowels as in the modern “seat” or “mean,” but the meaning is the same as the modern “sight” or “mine.” Our long ‘O’ sound would be spelled in Middle English with “o” or “oo” if it is the “close o:” Middle English “boot” would rhyme with “moat” or “boat.” As would, incidentally, the Middle English “fot” that you would put in the “boot.” The open ‘o’ had a sound like the ‘a’ in “law,” i.e. somewhere above uh and below ah. So a Middle English “lof” of bread may have sounded more like a lawf of bread. Finally, our modern words “house” and “flower” would have been pronounced in Middle English with a long ‘U’ sound although spelled with the same “ou” or just “u.” So one might have brought a “flour” into the “hus” (a “flower” into the “house”) to brighten Mom’s day, but it would have sounded like you brought a flure into the hoose.

Missing or Silent Letters in Middle English

The rapid change from Chaucer’s Middle English to our Modern English left behind many peculiar artifacts.

For example, Middle English speakers pronounced the silent letters of Modern English, such as the ‘k’ in “knife”—Middle English’s “knif.” A modern reader of Middle English’s “knif,” therefore, must understand that it is a two-syllable word that rhymes with “beef:” a k-neef.

Speaking of silent letters, the rather silent Modern English “knight” would have been a three-syllable k-nee-gcht. Part of the reason for the oddity of our “knight” is the presence of the silent ‘gh.’

Part of the reason ‘gh’ is such a ghastly, thoroughly conghusing (sorry) letter combination in English is due to a Middle English letter we no longer use: ‘Yogh’ (Ȝ). Another Middle English spelling of “knight” uses the letter yogh: “kniȝt.”

‘Ȝ’ could stand for the sound of our modern ‘y,’ or the sound of a throaty ‘gh’ (no longer used in most contemporary English). Yuck—or should I say Yogh (or yuȝ)!

Modern English turned the throaty ‘gh’ sound into a hard ‘g,’ such as in the formerly throatier ‘g’ of “ghosts.” Are you aghast?

The lowercase character for Yogh, ȝ, also looked like a fancy ‘z’ when printed, so the name MacKenȝie, originally pronounced “MacKenyie,” has earned a foreign ‘z’ sound over the last few centuries.

Middle English Literature’s Leftovers

The Great Vowel Shift affected most long vowels, but there are exceptions. One knows how to say the ‘ou’ in “house” aloud after the Great Vowel Shift, but why not pronounce ou the same way in “group?” “Group” simply stuck with the Middle English pronunciation, like a pebble in one of our shoen, although we would no longer say, “There’s a moose loose in the hoose!” when a mouse scurries through our house.

Likewise, another odd vowel sound that survived The Great Vowel Shift would be the Middle English pronunciation of the ‘ea’ in “steak.” Strange that the long ‘A’ sound of steak lives on in the meat that you eat, riȝt?

And, lastly, while Modern English usually adds an ‘s’ to make a word plural, like my “eye” becoming both “eyes,” Middle English continued to add the Germanic ‘-en,’ holdovers of which confuse students of English to this day. Right, children?

The Middle English plural word for eye, “eie,” was “eien” until it finally became “eies.” But we are stuck with “children.” Thankfully, we wear shoes instead of shoen, though.

What are Representative Works of Middle English Literature?

Obviously, studying Middle English can shed light on any number of the complexities of our modern language. In fact, the rich blending of at least two vocabularies, the Germanic and the French, gives English a wonderful variety of second domain words, and the mixing of grammatical systems, perhaps, a versatile way to express them syntactically.

Moreover, the stories and concerns of the Middle Ages—knights and castles, kings and queens, chivalry and ladies faire—influence the content of later literature written in English. Consequently, knowing stories and poems of the Middle English period will help one understand the conversation going on in later periods, just as reading Ancient and Classical literature builds one’s base of knowledge for understanding literature from all the later periods.

For all of these reasons, and perhaps because they are simply great fun to enjoy, taking the time to read representative works from the Middle English period will help you think like a reader.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and “Pearl”

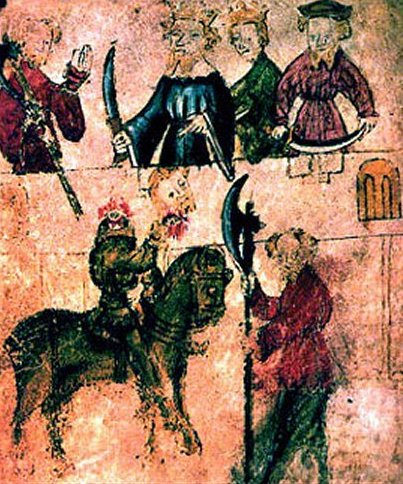

When a mysterious green knight bursts into King Arthur’s court at Christmas, Sir Gawain accepts his challenge: he may strike off the Green Knight’s head with a battle axe, but the Green Knight must have the opportunity to return the blow one year later. Imagine Sir Gawain’s surprise when the headless Green Knight rides away, demanding his promise be fulfilled in a year!

J.R.R. Tolkien’s translation into Modern English maintains the accentual verse, rhyme scheme, and alliteration of the Middle English. He maintains the famous “Bob and Wheel” verse form that ends every stanza with a punch. Wherever the literal meaning of a line may have come at the expense of the remarkable prosody of the Gawain Poet’s art, Tolkien went with the power of poetry, making this the best translation of the original into Modern English.

The anonymous Gawain Poet also wrote another, quite different Middle English masterpiece that has survived: “Pearl.” In it, a grieving father sits by his daughter’s grave. In the face of devastating loss, he has a phantasmagoric dream in which his daughter, Pearl, lives on in the splendid kingdom of God. Editions of Tolkien’s Sir Gawain and the Green Knight usually include his translation of this gem as well.

“For the head in his hand he holds right up;/Toward the first on the dais directs he the face,/ And it lifted up its lids, and looked with wide eyes,/And said as much with its mouth as now you may hear:”

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (Illustration from the Cotton MS, c.1400; translated by Marie Borroff)

John Barbour’s The Brus

Five centuries before he appeared fighting alongside William Wallace in Mel Gibson’s movie Braveheart, Scotland’s hero-king Robert the Bruce was immortalized in John Barbour’s long poem, The Brus.

Despite being the exciting tale of Robert the Bruce’s fight for Scotland’s freedom from England, this poem is written in Early Scots. Early Scots developed out of a dialect of Middle English called Northumbrian, and is the ancestor of the current Scots language. Should one not want to commit to the whole 14,000 line poem, a reading of book 12, with its climactic battle at Bannockburn, will give curious readers a look at the branching out of the English language that would flower into the Scots language spoken today in Scotland.

“Fowles in the Frith”

This little five-line poem has been found on a single page, in a single manuscript, from the 1200s. In a book full of legal matters, some scribe had jotted down a song he had heard. This is fortunate for us.

There are precious few lyric poems from the early Middle English period; moreover, “Fowles in the Frith” is even more remarkable as it also has included a musical score for two voices. Hearing it gives us a rare living example of a bit of music and poetry direct from the Middle Ages.

Fowles in the frith, The fisses in the flod, And I mon waxe wod. Much sorw I walke with For beste of bon and blod. Birds in the trees, The fishes in the flood, And I might grow mad. Much sorrow I walk with For a beast of bone and blood.

There is wordplay in the original song a reader should consider when using my translation above (or any translation). To “wax” is to grow, and the Middle English “wod” meant “mad” or “insane,” but also could have meant “wood” as from the trees of the “frith” or forest of line one.

The final line’s “beste” may be read as “beast,” as I have given it, but it might also be read “best.” Does the poem sing the song of a person alienated from nature, full of worries the birds and fish do not have? Or is the speaker attracted to another human “beast?” Is he or she therefore the “best of bone and blood” for the poet? Is the singer becoming wood, i.e. going mad with natural instinct? Is “Foweles in the Frith” a love poem, a song of existential anguish, or both at the same time?

Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales

A diverse group of English characters on a holy pilgrimage to Canterbury to honor St. Becket fall in together and decide to tell stories to pass the time. This simple set-up allows Geoffrey Chaucer to spin yarns that have delighted readers of English for centuries.

Subjects range from the chivalry and honor of the Knight’s Tale to the low humor of the Miller’s Tale (itself structured like a long, naughty joke). Perhaps the remarkable bird’s eye view of all parts of society, high to low, alone would make this the most important work of Middle English literature.

As England’s first printed book, however, it has influenced not only the content of subsequent stories in English, but affected the development of the English language itself. The characters often seem to chide or complement one another’s stories, making the whole of The Canterbury Tales worth reading straight through.

Those who would rather just sample The Canterbury Tales, however, might read the short General Prologue and then focus on “The Knight’s Tale,” “The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” and “The Friar’s Tale” to see how the so-called three estates of England in the Middle Ages, the nobility, the commoners, and the clergy, are brought together by Chaucer in a generally humorous clash of perspectives.

Representative Works of Middle English Literature

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and “Pearl,” “Fowles in the Frith,” John Barbour’s The Brus (Scots English), and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.