Point of view identifies the vantage from which a work of narrative, exposition, drama, or poetry is told.

Point of view refers to the technical vantage point specifically: first person (“I”), second person (“You”), or third person (“He,” “She,” “It”).

As one of the elements of literature, point of view must be considered in any worthy close reading.

Find out more about point of view in narrative, exposition, drama, or poetry below. Alternatively, click to move on to the next literary element, imagery.

Though I’ve written many novels in the third person, I’ve never felt as close to the characters as I felt to Louis.

Anne Rice

Point of View versus Perspective

Point of view often is written as if it were a synonym for “perspective,” and vice versa. Perspective, however, more precisely describes the world view offered by a particular character or author.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for example, is written from the first-person point of view of Huck. His perspective is that of a twelve-year old, semi-literate runaway in the antebellum South. His companion Jim, an adult father and runaway slave, has a rather different perspective from Huck. Part of the novel’s value comes from understanding Jim’s perspective by close reading for an ironic understanding of Huck’s words.

Huck sometimes misunderstands Jim’s perspective; it is vital the reader does not.

Point of View in Narrative

First Person

If first person point of view, the story may be told by a major participant. The major participant is usually the protagonist, such as David Copperfield in the novel of the same name. A first-person minor participant is someone who observes and reports on the main character. Minor participants include Ishmael who reports on Captain Ahab’s disastrous pursuit of the white whale in Moby-Dick. In either case, the speaker relies on the pronoun “I.”

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show. —Charles Dickens, David Copperfield

Call me Ishmael. —Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Some authors have used the first-person plural point of view successfully:

We remembered all the young men her father had driven away, and we knew that with nothing left, she would have to cling to that which had robbed her, as people will. —William Faulkner, “A Rose for Emily”

Third Person

In third-person omniscient (“all knowing”) point of view, all of the thoughts and feelings of every character are conveyed. Third-person limited omniscient, on the other hand, conveys the thoughts and feelings of a particular character only, usually the protagonist. Finally, in third-person objective, the author conveys the actions of the characters but not their inner voices or feelings. This last is less typical in narrative fiction, though Ernest Hemingway employed an objective style to great effect in stories such as “Hills Like White Elephants.”

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” —Jane Austen

Second Person

You realize second-person point of view is rare.

You look at this page, and you wonder how the author knows what you are thinking or doing, anyway.

Point of View in Exposition

First Person Exposition

Despite the advice that exposition should be told from an unbiased (sounding) third-person point of view, some of the best scientific and philosophical writing has been told from the first-person point of view.

To my mind it accords better with what we know of the laws impressed on matter by the Creator, that the production and extinction of the past and present inhabitants of the world should have been due to secondary causes, like those determining the birth and death of the individual. —Charles Darwin, Origin of Species

Life is a series of surprises. We do not guess today the mood, the pleasure, the power of tomorrow…. —Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Circles”

Third Person Exposition

Third person point of view may be the default point of view for most forms of contemporary exposition. News articles, textbooks, and academic essays often surrender themselves to the third-person point of view’s promise of objectivity.

Second Person Exposition

The humble instruction manual or how-to video would be lost without the imperative command of the second-person point of view.

Turn the new lightbulb clockwise until it is fully seated in the socket.

Point of View in Drama

Dramatic Point of View

Playwrights often work in the dramatic point of view, also called third-person objective. In it, they present characters’ actions on stage or screen with no other insight into their inward thoughts or feelings apart from what they do or say.

Francis Ford Coppola’s film The Godfather

Oscar Wilde’s play The Importance of Being Earnest gives little outside of dialogue and stage direction for its characters.

Third Person in Drama

Since drama imitates action, the point of view may seem confined to the third person objective, but there are complications.

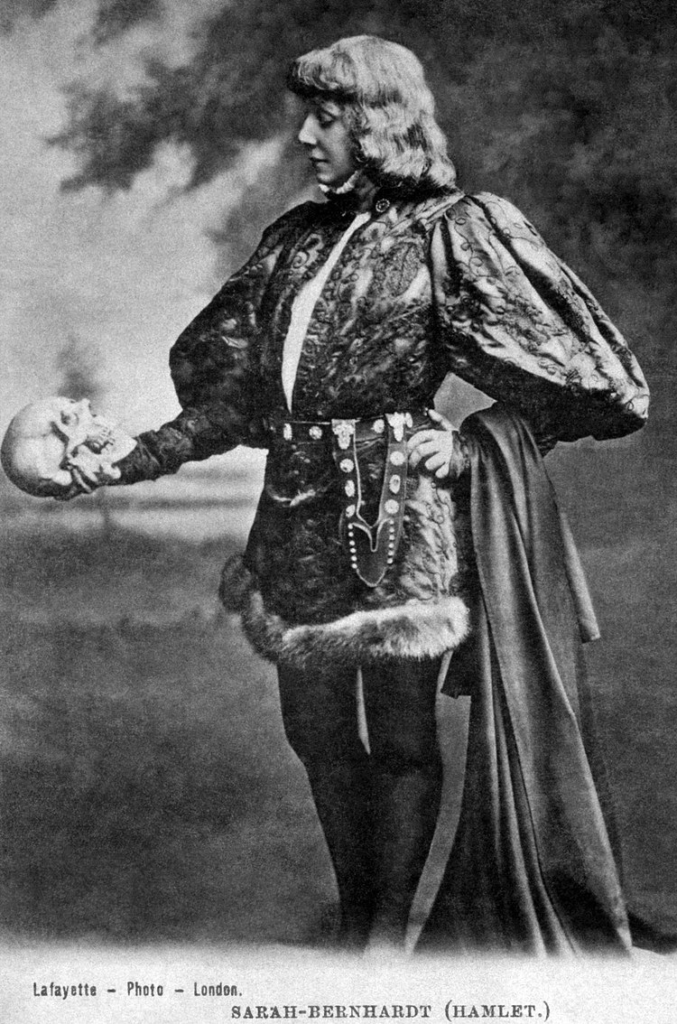

Apart from the dramtic point of view, other uses of the third-person point of view in drama may rely on voiceovers by an independent narrator or a character, or on characters speaking their thoughts aloud while alone—i.e. the soliloquy (“talking alone”)—to relate inner thoughts or feelings.

Drama may therefore employ third-person omniscient or third-person limited omniscient with voiceovers and soliloquies.

Arthur Miller’s play Death of a Salesman uses voiceovers and fantasy sequences on stage to depict protagonist Willie Loman’s descent into dementia from his inner point of view.

Point of View in Poetry

Lyric Poems

The lyric poem is a short poem, sung in ancient times by a poet playing a lyre (a stringed instrument). Furthermore, it is sung from the first-person point of view.

In the 7th century BC, Sappho sang her experience with metaphors of love and then Archilochos sang in his rough, soldier’s voice of love and combat, and now, thirty centuries later, popular music stars strum guitars and sing their experience with metaphors of love and rap artists sing of love and combat.

There are many sugenres of the lyric. Examples include the ode (a lyric paying homage to something or someone) and the elegy (a lyric expressing sorrow over a loss, especially a death).

So long as an “I” directly addresses the reader or listener, telling him or her about an important or urgent experience, the poem is in a lyric mode.

My tongue sticks to my dry mouth,/Thin fire spreads beneath my skin,/My eyes cannot see and my aching ears/Roar in their labyrinths. —Sappho1

The gods toughen us, Pericles,/To stand this pain. Fortune, misfortune;/ Misfortune, fortune. Grit your teeth. —Archilochos2

The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face/Where these visions of Johanna have now taken my place. —Bob Dylan

Visions of Martin Luther staring at me,/ Malcolm X put a hex on my future,/someone catch me. —Kendrick Lamar

Expository Poems

Apostrophe addresses someone or something that is not present.

Frederick Douglass pours out his anguish to sailboats moving far over the horizon, “You are loosed from your moorings, and are free; I am fast in my chains, and am a slave!”

Narrative Poems

Some of the earliest poetry in Western literature is epic poetry. Epics tell long, narrative stories about heroic deeds, typically from the third person point of view.

Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey, for example, use third-person omniscient (“all knowing”). All of the thoughts and feelings of every character are conveyed: even gods.

In the bright hall of Zeus upon Olympos/the other gods were all at home, and Zeus,/the father of gods and men, made conversation. —Homer3

Dramatic Poems

Apart from the epics, some of the other earliest poetry in Western literature was written to be performed: dramatic poetry.

Sophocles, for example, wrote his plays for performance. His early verse plays, however, differed from later third-person perspective in drama with the use of the chorus, actors who would sing the poetic lines as a group, commenting on the action, thoughts and feelings of the characters, and the moral conflicts unfolding on the stage.

O citizens of Thebes, this is Oedipus,/who solved the famous riddle, who held more power than any mortal./See what he is: all men gazed on his fortunate life,/all men envied him, but look at him, look. —Sophocles4

Later dramatic poems might not have been intended for performance on stage, but feature a character delivering a monologue. Robert Browning’s famous monologues address us from the first-person point of view. The reader must imagine the scene.

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,/Looking as if she were alive. —Browning