Diction means “word choice.”

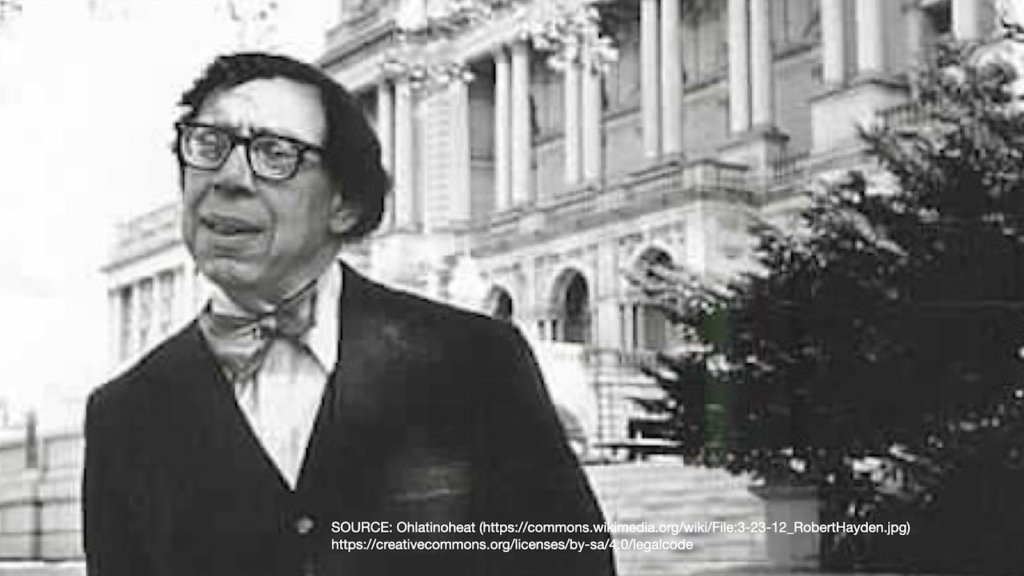

Paying attention to a particular word and the way an author uses it helps tremendously in understanding a text. When Robert Hayden closes his poem “Those Winter Sundays” by saying he did not understand as a boy “love’s austere and lonely offices,” we might wonder why the poet chose the word “austere.”

Connotation and First Tier Diction

When we encounter an unfamiliar word, we might guess at its meaning from context, forming a connotative, or implied but inexact, definition.

This may work very early in elementary school, when one is just learning to read and encountering the first tier of vocabulary, i.e. simple words; more advanced students, however, should seek out a precise definition from a dictionary in order to find a denotative, or explicit and exact, definition–especially as they encounter second tier vocabulary, i.e. more complex words—in their reading.

Of course, language is always changing, and writers rely on subtleties of meaning and connotation to make their art. Ultimately, connotative and denotative meanings should work together when close reading.

Getting back to Hayden’s poem, “austere” may mean “stern and sober” or “morally strict,” all of which may apply to the father in the poem, who gets up very early on Sundays to polish his son’s shoes for churchgoing.

But “austere” also means “simple and unadorned.” In the end, the father’s love was simple and unadorned, something the speaker of the poem may not have appreciated when he was a child who focused more on his father’s stern and sober, morally strict qualities.

Denotation and Second Tier Diction

“Austere” comes from the second tier of vocabulary: complex words, often with more than one meaning. While “cat” and “book,” “catch” and “sit” are all first tier words, others such as “cacophony” and “adamantine,” “meditate” and “echelon” are firmly in the second tier.

Words from the first tier are quite common, and we learn them primarily through speaking with our parents and peers as children. Words from the second tier are still common, but they have more complex definitions or multiple meanings, and we learn them primarily by reading. Some second-tier words, in fact, originate in literary stories, e.g. “procrustean” or “protean.”

Reading and learning new second tier words by looking them up may be a painstaking process, but the reward is a more precise vocabulary and so more precise thinking.

Use the right word, not its second cousin.

Mark Twain

Third Tier Diction

Finally, the third tier of vocabulary refers to words applied in a specific discipline. This tier does not

consist of jargon, which is deliberately obscure and pretentious, but rather a technical vocabulary intended to clarify highly specialized, complex thinking and make it more precise in a specific discipline.

When learning mathematics, words such as “vector,” “formula,” and “variable” take on specific meanings. They are third-tier words. This website, also, deals with vocabulary in the third tier from the discipline of English literary study, such as the list of figures of speech in the previous section.

Some writers, Ernest Hemingway for example, write splendidly using fairly basic diction, achieving a spare prose style. Others, Nathaniel Hawthorne for example, use more words from the second tier.

Whatever a given writer’s style, when we close read for diction, we ask, “What are all the meanings of that word?”

So, does Hayden mean the father’s love in “Those Winter Sundays” was “stern and sober,” “morally strict,” or “simple and unadorned?”

When close reading for diction, we realize that “austere” in the case of this father’s love means all three.

DICTIONARY, n. A malevolent literary device for cramping the growth of a language and making it hard and inelastic.

Ambrose Bierce